The Oxford of West Africa

- Bruce Boyce

- Nov 21, 2020

- 5 min read

Updated: May 15, 2022

"There are in Timbuktu numerous judges, teachers and priests, all properly appointed by the king. He greatly honors learning. Many hand-written books imported from Barbary are also sold. There is more profit made from this commerce than from all other merchandise."

Leo Africanus (El Hasan ben Muhammed el-Wazzan-ez-Zayyati ), 1526

Timbuktu. In English, it has become a metaphor for a faraway distant place. Yet at one time, Timbuktu was a center of culture and learning in West Africa.

Timbuktu today is in the country of Mali. Its origins are unclear, but most scholars believe that it was settled by Taureg nomads as a caravan stop. By the 12th century, the city was an important center along the Arabian-African trade routes of Sub-Sahara Africa. Commodities included salt, gold, ivory, and slaves. Because of this position, the city converted to the Islamic religion. Early in the 14th century, the region was taken over by the leaders of the Mali Empire. The Mali Empire arose a century earlier from the upper reaches of the Niger River under the leadership of Sundiata Keita. After Sundiata, Mali rulers took on the title of Mansa, meaning king or emperor.

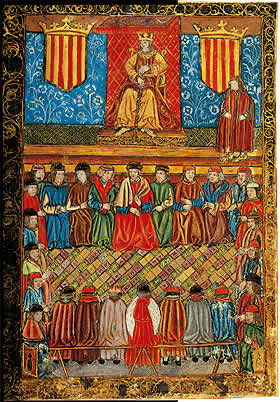

During the reign of his nephew Mansa Musa I, the Mali Empire reached its zenith of influence and power. Musa is reputed to be perhaps one of the wealthiest persons in history. He was also a very devout Muslim, and he made a pilgrimage to Mecca between 1324 and 1325. He became well known in the North African Arab world during his journey, and he established a relationship with Cairo, then the largest gold market. Musa saw Islam as the gateway to the culture and learning of the Eastern Mediterranean. He brought much of that back with him to Mali. Upon his return, he annexed Timbuktu, and he built a royal palace and a mosque. He also helped establish madrasas in the city. A madrasa is a place of instruction, in particular the Islamic religion. In medieval times, madrasas served to teach Islamic law.

Timbuktu, under Mali imperial leadership, grew to become a center of Islamic scholarship. This continued after the Songhai Empire succeeded in taking over the region. Under the Songhai King Askia Mohammed, the city would reach its peak in the 16th century. The 17th-century Arabic history of the city, the Tariqh al-Sudan, noted that Timbuktu was "a refuge of scholarly and righteous folk, a haunt of saints and ascetics, and a meeting place for caravans and boats."

Into this atmosphere of scholarship, Mohammed abu Bakr al-Wangari came to Timbuktu to teach at the Sankore Madrasa. The madrasa, one of the many founded by Mansa Musa I, was associated with the Sankore Mosque which dated back to the late 10th century. Al-Wangari helped expand the madrasa into a university, but unlike European universities, there was no central administration. Rather it was a loose confederation of the city mosques and private homes each headed by its own master, or imam. Students were assigned a single teacher, and classes were conducted in open courtyards. The principal lessons were in studying the Koran as well as Islamic law and literature. Other subjects included medicine, mathematics, philosophy, and geography. Al-Wangari was a collector of books. He imported thousands of volumes of works on various subjects from history to astronomy. He would pass these on to his sons and eventually, they were spread out among descendants. Through his efforts and others, Timbuktu had come to rival the learning centers of Oxford and Paris in Europe and Cairo and Istanbul in the Arab world. Students came from all parts of the Islamic world. Historians set down accounts of Saharan and Sudanese kings. Astronomers charted the stars. Physicians studied the medicinal properties of desert plants.

Unfortunately, by the end of the 16th century, the heyday of Timbuktu's intellectual culture came to an end. The city was conquered by mercenaries from the Sultanate of Morroco. Morrocan leaders put to death many Timbuktu scholars fearing them to be subversive to the new regime. Many others were brought to the Morrocan court. This exodus of intellectual capital started the city's decline. Its prominence as a trading center soon waned as trade routes shifted to the coasts and ocean-going routes. Over time Timbuktu faded into obscurity. Because of its inland position, it became difficult to get to and more isolated. The city turned into a myth outside of Africa. For Europeans, it became like an African El Dorado. It was a legendary city of untold riches and wealth. Explorer after explorer sought to find it. The terrain, though, was not the only obstacle. Non-Islamic visitors were not welcome in the region. It would not be until early in the 19th century that European explorers discovered the city, many of them disguised as Muslims. What they found was not a golden city, but one that was slowly crumbling back into the desert. There were some remnants of Timbuktu's heyday as a center of learning. Some of the manuscripts were smuggled out by the French to museums, but by and large, the wealth of books was largely forgotten. The volumes of books once traded in the bazaars of the city disappeared to be hidden in trunks or cached away in the desert to protect them from successive conquerors and colonial invaders.

Today the Timbuktu manuscripts are beset by the threats of climate change, increased desertification in the region, civil unrest, and terrorism. There are many efforts to help find, restore, and preserve these texts. Starting in 1964, after Mali gained independence from France, UNESCO sought to gather and protect the region's lost writings. They helped establish archives in the area. In the late '90s, these archives received grant money from places like the Ford Foundation and the Andrew Mellon Foundation. The money went toward expanding libraries and promoting access to the texts. A descendent of al-Wangari is working on gathering al-Wangari's collection that has been scattered among the family for generations. Others are trying to recover texts damaged by centuries of mold and water damage. And others are trying to protect manuscripts from falling into the hands of Islamic extremists. Timbuktu is now a World Heritage site but also has made the list of one the most endangered sites. The goal of many of these efforts is not only to preserve these texts but also to bring attention to their historic significance. Many believe that these manuscripts can help bridge the gap of understanding between Islam and the West.

We often think our interconnected world is something new. The world has always been connected, not necessarily through Europe. Trade routes, no matter the time period, have always been not only for the movement of goods but avenues for the flow of ideas and the exchange of cultures. Timbuktu grew into a great intellectual and cultural hub because of its contacts with the broader world. When those contacts disappeared or were severed, the city faded into memory. Now it is a place that is hard to reach. Yet Timbuktu and its place in history challenge our notions of Africa and its people.

Further Reading:

The Treasures of Timbuktu: Joshua Hammer (Smithsonian Magazine)

Life in Timbuktu: Alex Duval Smith (The Guardian)

A Guide to Timbuktu: National Geographic

Timbuktu, World Heritage Site: UNESCO

Looking for the perfect sofa to complete your living room? Look no further! At Abhiandoak, we offer a stunning collection of high-quality sofas designed for comfort and style. Whether you're searching for a modern loveseat or a spacious sectional, you'll find it here. Buy sofa set from us and transform your home today! Explore our wide range of designs, colors, and materials. Plus, enjoy exclusive discounts and fast, reliable delivery right to your doorstep. Shop now and experience the ultimate in comfort and elegance.

This new collection of time-and-date and chronograph models features a Clous de Paris pattern link on the dial, giving it a bit of texture compared to the previously flat dials. Bulgari plays it down the middle with dial colors: the time-and-date Octo Roma will be offered with a blue, anthracite, or white dial, while the chronograph will be offered with a black or link blue link dial.

Caliber: LF270.01Functions: Hours, minutes, small seconds, dateDiameter: 31.6mmThickness: 4.85mmPower Reserve: 72 link hoursWinding: AutomaticFrequency: link 28,800 vph (4 Hz)Jewels: 31Number of link components: 215

If you want to rewind all the way back to 2011 and see link where it all began, feel free to take a scenic detour to this article from the early Hodinkee days, and before Ressence went crown-less. Also, I will do my best link to articulate how to set link the time but feel free to play around with the time-setting simulator on the brand's website to get a more interactive experience.

There's one Omega link release that hasn't gotten the attention it deserves, partly because it's link just a new colorway: The new Omega Seamaster Diver 300m with a green dial, green bezel, and link even greener rubber strap.