Juana of Castile Reconsidered

- Bruce Boyce

- Nov 26, 2025

- 10 min read

Madness, Gender, and Power in Early Modern Europe

In August 1520, rebels took control of Tordesillas castle and freed the woman imprisoned inside. For fourteen years, Queen Juana of Castile had been held captive, declared too mentally unstable to rule the kingdom she had rightfully inherited. Her captors spread stories of madness, uncontrollable passions, and religious delusions. But when the comuneros—Castilian rebels fighting Emperor Charles V—actually spoke with Juana, they found a woman who, as notarized attestations recorded, spoke with clear intelligence and sound judgment.

For 103 days in 1520, the truth about Juana nearly broke through. Then imperial forces recaptured Tordesillas, the doors closed again, and Juana spent thirty-five more years in captivity. She died in 1555, having nominally ruled Castile for forty-nine years but governed none of them. History remembered her as "Juana la Loca"—Joanna the Mad—a tragic romantic figure driven insane by grief over her unfaithful husband.

In the twenty-first century, historians finally reopened those doors. What they found wasn't madness but conspiracy—documented, systematic, and devastatingly effective. Modern scholarship shows Juana not as a mentally ill woman who needed confinement but as a sane queen whose legitimate power threatened every powerful man around her. Her story reveals how "madness" was used as a political weapon against inconvenient women in early modern Europe—and raises uncomfortable questions about how little has changed.

Juana was born in 1479 as the third child of Isabel I of Castile and Fernando II of Aragon. Well-educated, multilingual, and trained in court diplomacy, she was never expected to ascend to the throne. In 1496, she married Philippe the Handsome, Duke of Burgundy and heir to the Habsburg territories, in a strategic alliance that would reshape European politics.

Then tragedy struck. Her older brother, Juan, died in 1497, followed by her elder sister, Isabel, in 1498, and Isabel's infant son, Miguel, in 1500. Suddenly, Juana was first in line to inherit Castile, one of Europe's wealthiest kingdoms.

When Isabel I died on November 26, 1504, Juana became Queen of Castile. Right away, the problems started.

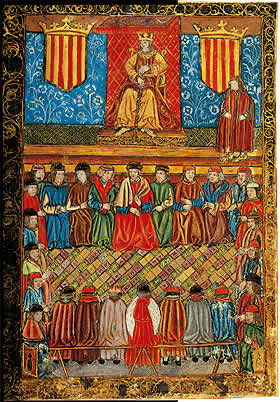

Fernando co-ruled Castile with Isabel for thirty years, but Castilian law was clear: his authority came from his wife, not his own right. Isabel's will allowed him to continue governing only if Juana was "absent" or "unwilling to rule." Within months, Fernando convinced the Cortes of Toro in 1505 that Juana's illness prevented her from ruling, so he made himself regent.

Philippe the Handsome had his own ambitions. He aimed to become king in his own right, not just his wife's consort. By early 1506, both men were spreading rumors about Juana's mental instability—and, notably, about each other's attempts to spread those rumors. A state document quotes Philippe accusing his father-in-law directly: Fernando "takes care that a rumour be spread that the Queen his daughter is mad, and that he is consequently entitled to govern in her stead."

Philippe, Duke of Burgundy (left); Fernando of Aragon (Right)

On June 27, 1506, two men met at Villafáfila to negotiate a treaty. The public document showed Fernando ceding Castile to Philippe and Juana. Still, a secret clause revealed both agreed Juana's 'infirmities and sufferings'—noted as 'for the sake of honour'—made her incapable of ruling. They also decided that if Juana tried to interfere, they'd prevent it. Later, Fernando secretly declared the treaty void before a notary.

Three months later, Philippe died suddenly at age twenty-eight. Pregnant with her sixth child, Juana initially tried to exercise royal authority by revoking Philippe's concessions and expelling his Flemish courtiers. But Fernando waited strategically as plague and famine ravaged Castile, allowing chaos to make his return seem necessary. In 1509, he ordered his daughter to be confined to Tordesillas.

When Fernando died in 1516, Juana's son, Charles, became king. He kept his mother imprisoned until she died in 1555. She had been Queen of Castile for forty-nine years, but spent forty-six of those years in captivity.

For centuries, this story was seen as a romantic tragedy. The nineteenth century embraced Juana as the ideal heroine of doomed love. Spanish painter Francisco Pradilla's 1877 canvas Doña Juana la Loca immortalized the iconic image now in the Prado: a windswept queen in black, standing over her husband's coffin in a barren landscape, surrounded by flickering torches.

Art historian María Elena Soliño argues that Pradilla's work served political purposes beyond romanticism. Created to celebrate Alfonso XII's marriage, it depicted royal female passivity and helplessness, helping erase memories of Queen Isabel II's reign and "unruly female sovereignty." The mad queen, overwhelmed by grief and unable to rule, was considered safer than a competent woman whose throne was stolen.

The nineteenth and early twentieth centuries relentlessly expanded the legend. The most sensational part—repeated in plays, operas, and novels—was the corpse story. According to this tale, Juana traveled across Castile with Philippe's embalmed body, repeatedly opening the coffin to look at him, sometimes kissing his feet. She supposedly kept any woman away out of posthumous jealousy. The story perfectly reflected Victorian ideas about feminine emotional excess and the supposed dangers of female passion unchecked by male authority.

The first major challenge to the traditional story came from German historian Gustav Adolf Bergenroth, who worked in Spanish archives in the 1860s. Although he incorrectly proposed that Juana had been persecuted for Protestant sympathies instead of madness, his work asked the right question: what if the official story was wrong?

The definitive reassessment arrived in 2005 with Bethany Aram's Juana the Mad: Sovereignty and Dynasty in Renaissance Europe. A historian at the University of Seville, Aram spent years examining unedited Vatican and Burgundian archives, analyzing documents that previous scholars had ignored or dismissed. Her main argument was straightforward: "Standard chronicles and political correspondence regarding Juana should be questioned in light of their authors' political interests."

In other words: follow the money. Or more accurately, follow the throne.

Aram showed that every man who called Juana mentally unfit directly gained from that statement. Fernando needed her out of the way to keep his regency; after Villafáfila, he even married eighteen-year-old Germaine de Foix to produce an Aragonese heir who would prevent the Habsburgs from inheriting his kingdom. Philippe needed Juana pushed aside so he could go from king consort to king. Charles needed to imprison his mother to claim her throne without her legitimacy challenging his authority.

The secret clause of the Treaty of Villafáfila provided written proof of a conspiracy. This wasn't just interpretation—it was concrete evidence that two men had officially agreed to prevent a queen from "meddling" in the government of her own kingdom.

Gillian Fleming of the London School of Economics expanded these ideas in her 2018 book Juana I: Legitimacy and Conflict in Sixteenth-Century Castile. Fleming's response to "Was Juana mad?" is, as a reviewer said, "a well-supported, rather convincing, and resounding 'no.'" While Aram saw Juana's seclusion as rooted in religious piety, Fleming argues evidence shows Juana actively sought to exercise her rights, govern independently, and oppose her relatives' usurpation.

The scholarly consensus has changed significantly. Historians no longer question whether Juana had a mental illness. They are now exploring how accusations of madness served as what Aram calls "a flexible concept in the realm of sovereignty"—a political tool used to diminish legitimate female authority.

The strongest evidence comes from the documented conditions of Juana's imprisonment and the testimony of those who actually interacted with her.

If Juana was truly insane and her confinement was meant as protective care, the conditions at Tordesillas seem illogical. Her first jailer, Mosén Ferrer, told Cardinal Cisneros that he had used "la cuerda"—a form of torture involving rope suspension and weights—on the Queen of Castile. When Cisneros investigated after Fernando died in 1516, he discovered that "such atrocities had been committed" and suspended Ferrer for "endangering the health and life of Her Highness."

Under Charles V's guardian, the Marquis of Denia, conditions barely improved. Juana was kept in "dark and ill lighted" rooms, forbidden to look out windows to avoid being seen or calling for help, and completely cut off from communication. The Marquis deceived her by falsely claiming Fernando was alive for four years after his death and fabricating letters from the deceased.

The Comuneros revolt of 1520 provided the clearest evidence. When rebels removed the Marquis and gained access to Tordesillas, they interviewed Juana's servants and spoke with the Queen directly. The testimony was unanimous and recorded in notarized attestations: Juana spoke clearly, wisely, and with good judgment.

Cardinal Adrian's report to Charles is clear: "Almost all the servants of the Queen said that she had been oppressed and detained by force during fourteen years... as though she had been mad, when in fact she had always been in her right mind, and as prudent as when she married." Adrian warned Charles bluntly that he faced "total and perpetual downfall" because "your Highness has usurped the Royal name, and imprisoned the Queen as though she were insane, when she was not mad."

But the most compelling sign of Juana's mental competence appeared in what happened next. For 103 days, the comuneros offered her freedom and political power, pleading with her to sign documents that would legitimize their rebellion and curtail Charles's authority. Day after day, Juana refused. She made excuses—claiming she needed to see specific provisions, wanting her council present, requesting different signatures—stalling skillfully until Charles's forces recaptured Tordesillas.

This wasn't madness. It was a strategic political calculation under extreme pressure. Juana protected her son—the man who had imprisoned her—from rebels offering her freedom. That shows not madness but painful, rational loyalty and a keen understanding of political consequences.

What about the famous corpse story—the most lurid and often cited "evidence" of her alleged necrophilia?

In a 2002 article titled "Juana 'the Mad,' the Clares, and the Carthusians: Revising a Necrophilic Legend," Bethany Aram carefully deconstructed this story by referencing contemporary documents instead of later embellishments.

The documented facts: Philippe died in Burgos in September 1506 and was embalmed in accordance with standard royal practice. Juana wanted to bury him in Granada, in the royal chapel beside Isabel's grave, as Philippe himself had specified in his will. In December 1506, she started transporting the coffin to Granada, traveling at night with torch-bearing attendants and resting during the day at monasteries—all standard protocol for royal funerals. The journey stopped at Torquemada in January 1507 when Juana gave birth to her sixth child, Catherine.

The well-known incident of "excluding women" from approaching the coffin has a simple explanation. Juana was staying at Carthusian monasteries and adhered to the Carthusian rule that prohibited women from being in the presence of the monks. This was misunderstood—or intentionally misrepresented—as a jealous exclusion of women from Philippe's body.

Most tellingly, after Philippe's body was laid in the Santa Clara church at Tordesillas, close to Juana's imprisonment, records show she "never expressed the least desire to visit his tomb." German historian Bergenroth, examining Spanish state documents in the 1860s, observed that she "mentioned his death just as any other widow would have mentioned the decease of her husband."

The woman, supposedly so unable to accept Philippe's death that she traveled with his corpse, showed no interest in visiting his grave when it was nearby. The corpse legend collapses under documentary scrutiny. Like much else in Juana's story, it was a later fabrication that served the narrative others wanted to tell about her.

Why was Juana's story believed so easily for so long? The answer lies in early modern—and modern—views on gender, emotion, and women's suitability for power.

Juana displayed behaviors that were pathologized explicitly because of her gender. She mourned her husband's passing, felt jealousy over his well-known infidelities, resisted some religious practices, and occasionally showed anger or depression. However, none of these behaviors would have disqualified a man from ruling.

The comparison with Philippe V of Spain is revealing. He endured severe and long-lasting episodes of depression, yet he ruled as King of Spain for nearly half the eighteenth century. No one seriously suggested removing him from office.

Juana faced what historian Gillian Fleming describes as systematic exploitation: she was "a complex figure whose sometimes emotional nature was exploited by the men around her as a way of limiting her ability to exercise her power as queen." Early modern medical theories, which blamed women's mental issues on the uterus—especially 'lovesickness'—provided a framework for this. Juana's love for Philippe and her depression after his death fit these gendered categories.

Inquisitors and theologians went further, linking female melancholy to spiritual deviation. Some accused Juana of Jewish sympathies or demonic possession. A woman whose emotions went beyond accepted limits wasn't just mentally ill—she was spiritually dangerous.

Bethany Aram's key theoretical contribution is demonstrating that "madness, like gender, proved a flexible concept in the realm of sovereignty." Both were categories that could be politically negotiated and used. Juana's grief became evidence of insanity. Her anger became proof of instability. Her resistance became confirmation of unfitness to rule. Every normal human emotion was weaponized against her claim to power.

Juana's story is important because the patterns it reveals still exist. Women in leadership roles still face questions about their emotional stability and fitness that men rarely encounter with the same severity or consequences.

A woman who holds or pursues legitimate power challenges current male interests. Her emotions—such as grief, anger, or straightforward resistance—are often seen as abnormal. This labeling is used to justify her removal. The system then dismisses her agency, claiming it is for her own good or for the protection of others.

What makes Juana's case particularly valuable is that we have the original documentary receipts. The secret clause at Villafáfila and the notarized testimony from 1520—these aren't matters of interpretation. They are preserved evidence of a conspiracy. They reveal exactly how "for your own good" rhetoric concealed political violence and theft of legitimate authority.

The reassessment of Juana shifts her story from a romantic tragedy to a documented political crime. The "Juana la Loca" legend benefited everyone except Juana herself. Fernando maintained control of Castile. Philippe briefly held the kingship. Charles inherited a unified Spanish empire. Nineteenth-century romantics found their tragic heroine of doomed passion. Yet, only Juana lost everything—forty-nine years as queen, forty-six of them in captivity.

Modern historians have finally reopened the doors that closed at Tordesillas in 1520. What they discover inside isn't madness but something more unsettling: a sane woman shattered by a conspiracy that stole her crown, her freedom, and nearly her story. We're left with difficult questions. How many other "mad" women in history were mainly politically inconvenient? What does it say that we still find the romantic version more comforting than the documented truth? Should we keep using the title "Juana la Loca" even in scholarship, thereby perpetuating the very slander that imprisoned her?

Perhaps history's harshest judgment isn't against Juana of Castile. Maybe it's against everyone—then and now—who found it easier to believe she was crazy than to admit she was imprisoned.

Further Reading:

Juana the Mad: Sovereignty and Dynasty in Renaissance Europe - Bethany Aram

Juana I: Legitimacy and Conflict in Sixteenth-Century Castile - Gillian Fleming

Comments