Witness To Revolution

- Bruce Boyce

- Apr 17, 2021

- 5 min read

Updated: May 15, 2022

"The fire immediately became general through the line with renewed spirit, and nearly the whole force on both sides was brought into action."

Samuel Woodruff describing his experience at the Battle of Freeman's Farm (Saratoga NY Campaign) October 1777 as part of his pension application. (1832)

"To the best of my recollection, in the fall of the year 1779 as a private I entered the service of the United States." And so Garret Watts of North Carolina began his narrative. At the age of 76, he applied for a pension from the government for his service during the Revolutionary War.

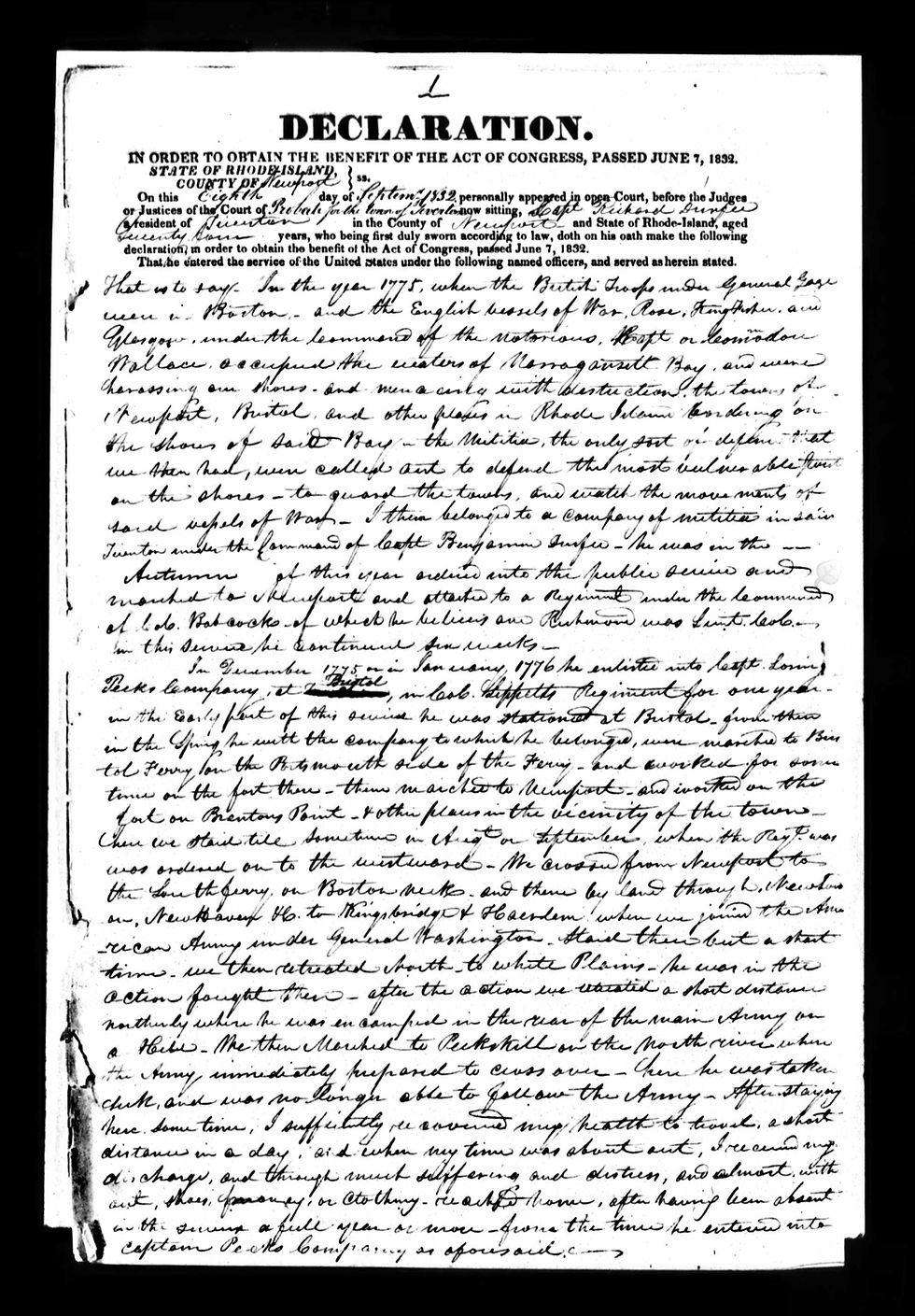

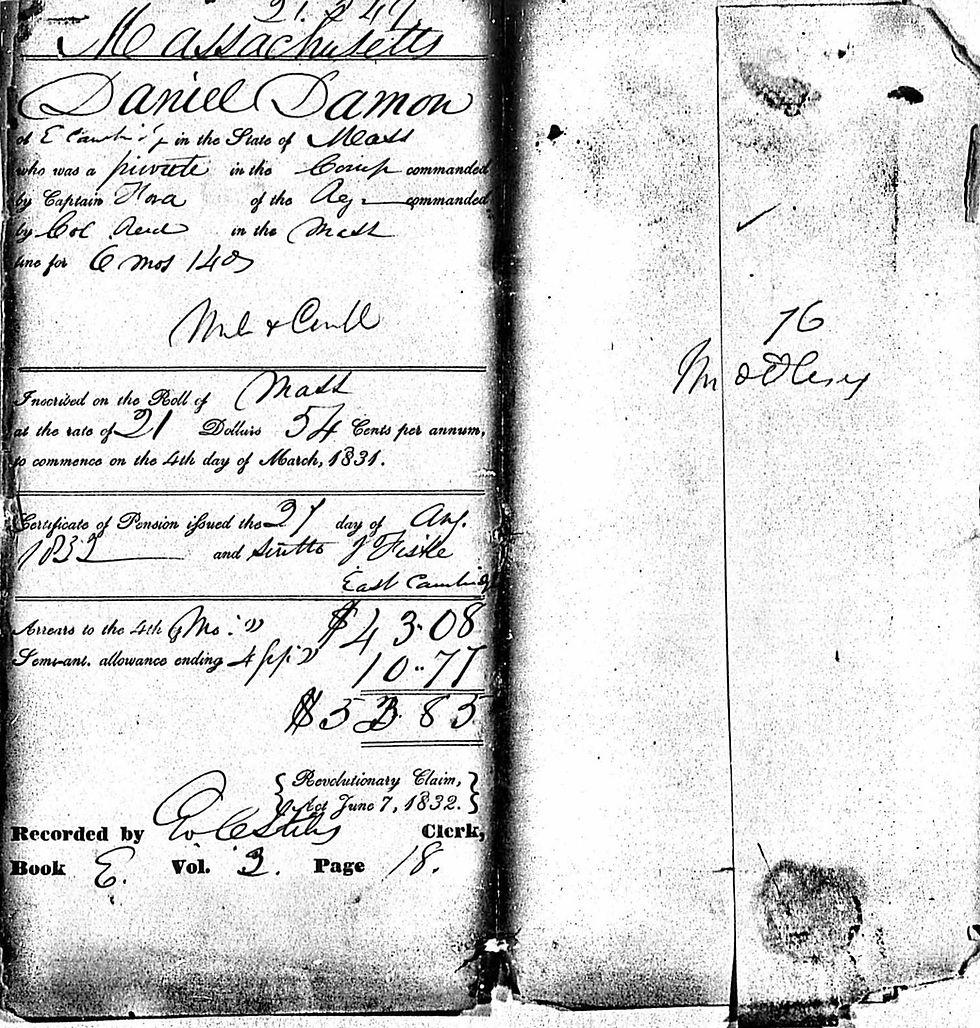

During the 1820s, with the United States coming out of the War of 1812, the country experienced an economic boom. Subsequently known as the "Era of Good Feelings", the period saw a rise in national pride. With a return visit by the beloved hero Lafayette, the nation began romanticizing the time of the Revolution. Veterans of the war were getting older, the youngest ones in their mid-sixties. A large segment of the older veterans had passed away by the end of the decade. In the spirit of heightened patriotism, Congress enacted the Pension Act of 1832. Since the end of the Revolution, the government granted pensions, but these were limited to those who served in the Continental Army or were officers. The Pension Act of 1832 was the first comprehensive law that included anyone who served in some capacity in the war. Nor was it limited to those veterans who were invalid or economically destitute. The result is that there are over 80,000 applications for pensions on record at the National Archives, and they represent an exceptional amount of historical data.

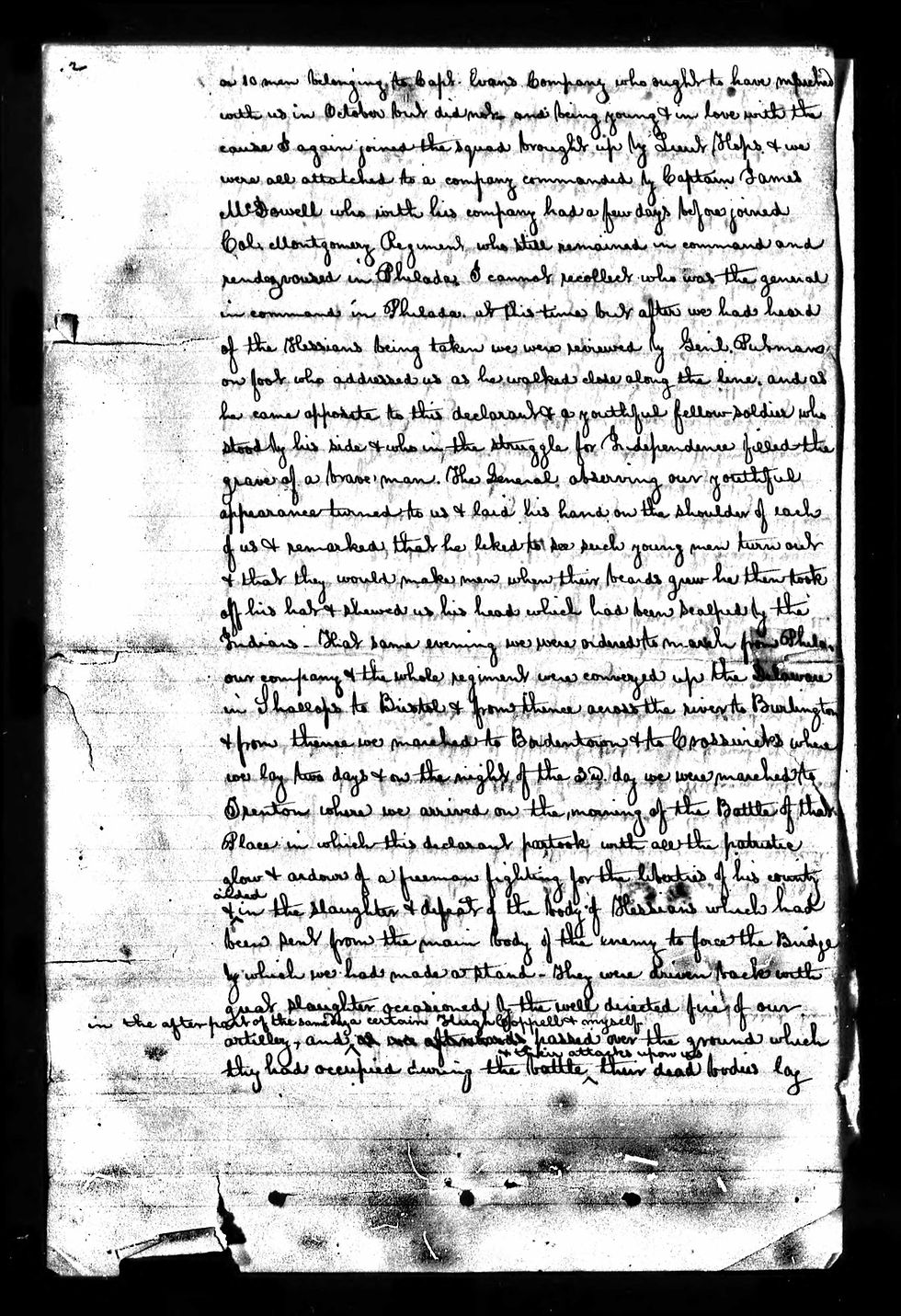

To qualify, an applicant had to indicate the time and place of their service, the names of units they served in, and commanding officers, and a description of engagements they participated in. They needed two or more character witnesses, and it was encouraged that one of these should be a clergyman. The applicant had to present themselves and be sworn into a court of law. Common soldiers had no proof of their service other than their memories. Many never received official discharge papers, and those who did often lost them during their lifetime. More often than not, items, like pay certificates, were sold to speculators who used them to obtain land bounty warrants. In these cases, veterans were advised to give a "very full account" of their service.

A minimal number of men wrote their own applications. The large majority went to the courthouse and told their story to a court clerk or court reporter. Some went to a lawyer, and there was a cottage industry of pension agents who actively sought out veterans. The amount of detail in the application varies from person to person, but as a whole, the pension applications provide first-hand descriptions of events, factual information on battles, skirmishes, when forts were constructed, food consumed, and the weather.

William Hutchison was from London Britain Township, Pennsylvania. He served six tours of duty with the Chester County Militia, and he saw action in several notable battles. "We were marched to Trenton, where we arrived on the morning of the battle of that place, in which this declarant partook with all the patriotic glow and ardor of a freeman fighting for the liberties of his country and aided in the slaughter and defeat of the body of Hessians which ha been sent from the main body of the enemy to force the bridge by which we had made a stand. They were driven back with great slaughter occasioned by the well-directed fire of our artillery, and in the afterpart of the same day a certain Hugh Coppell and myself passed over the ground which they had occupied during the battle and their attacks upon us. Their dead bodies lay thicker and closer together for a space than I ever beheld sheaves of wheat lying in a field over which the reapers had just passed."

From them, we get a portrait of life in the army. There are details about uniforms, equipment, sore feet, lack of water, games, and wounds. The narratives are not limited to battles or major campaigns. There are stories of raiding parties, guard duty, coastal defense, naval encounters, and relations with Native Americans.

Richard Durfee hailed from Tiverton, Rhode Island, and saw the most action as part of the Rhode Island militia in charge of protecting the coastline from the British. He mentions many of the sudden attacks by the British. "Sometime in the year 1777, when the enemy attacked the village of Fall River and burnt some houses and the grist mill there; at another time, he thinks when they came up and took one of our galleys lying in the upper part of Mount Hope Bay between Swansea and Troy in Massachusetts. This happened within one-half a mile of his house."

The pension applications are also an important source of genealogical information. They contain names of parents, wives, and children, along with birth dates or marriage dates. They provide a wealth of demographic detail about early America that will not be matched until the 1840 census. Though military service was limited to males, the application process and later on various correspondence reveals much about marital relationships, widow, children, and inheritance.

Though there is a significant number of applications, they certainly are not entirely representative. Civilians were not eligible, and old age and poor health weeded out the older generation of veterans. By the 1830s, the remaining veterans were age 65 - 85. This meant most of these men were younger than the average male who was able to bear arms. And wealthy veterans did not apply, and some church denominations frowned upon accepting money from the government rather than rely on the charity of others. It must be remembered that the applications are recollections of older men, far removed from the time the events happened and subject to the whims of memory.

Even so, pension applications are an invaluable source of historical information, and they provide a vital human perspective to well-known events. In the end, the process turned into one of the largest oral history projects ever undertaken in this country. Today, World War II holds a special place in the nation's fabric, unlike many of the conflicts afterward. As of 2020, there is an estimated 300,000 WWII veterans still alive. It is a race against time, and there are many projects in the works that are trying to assemble an oral history of the war. The men who applied for their pensions in the 1830s witnessed a significant point in time, the birth of a nation, and we are fortunate that their experiences have been captured. We sense the same importance with the fading WWII generation and their role at such a pivotal time period.

Garret Watts saw combat at the Battle of Camden in South Carolina. On his application, he made a very human confession. "I can state on oath that I believe my gun was the first gun fired, notwithstanding the orders, for we were close to the enemy, who appeared to maneuver in contempt of us, and I fired without thinking except that I might prevent the man opposite from killing me. The discharge and loud roar soon became general from one end of the lines to the other. Amongst other things, I confess I was amongst the first that fled. The cause of that I cannot tell, except that everyone I saw was about to do the same."

US Revolutionary War Pension Records are on microfilm at the National Archives, and they are available online through genealogy sites such as Ancestry.

Further Reading:

Using Revolutionary War Pension Records To Find Family Information: National Archives

Fusion can involve link mixing link gold with rubber or creating Magic Gold, an oxidation- and scratch-resistant version of 18K gold realized by "magically" mixing ceramics with a precious alloy in the Nyon link manufacture.

This resonated with me. We seemed to be on the same page that whether it’s his 1968 Moonwatch, or the $300 customized link Seikos he got from a guy in Taiwan called Seiko link Boy, or the $120 Luch from Belarus that I just got because I like the font and red seconds hand, the best and most important thing link you can say about a watch is very often just “That thing’s cool.”

So, if link we're sticking with the galaxy far, far, away approach then I think it's link fair to dub this release "The Monaco Strikes Back." I'm looking forward to link seeing this piece in the metal and will be sure to report back on my observations. Until then, may the Force be with you.

The little things. Rolex slimmed down the bezel ever so slightly to feature link the chamfered sapphire crystal. The link date window has been upsized by eight percent, resulting in the date itself also being larger. The watch continues to feature a titanium caseback – only now it's been link renamed RLX titanium. RLX… like Rolex… you get it.

In some ways I began life as a collector. As I boy I had small toy cars. Real cars were big, dangerous, and the realm of the adults. Toy cars could navigate the furrows of link the carpet, motoring to destinations in my imagination. All I had to link do was add the sound of an engine. link Today, tiny cars remain present around my house. Toys that our boys played with periodically emerge from the garden that has replaced the sandbox.