Vasco Da Gama

- Bruce Boyce

- Jul 18, 2021

- 6 min read

Updated: May 15, 2022

"When we arrived at Calicut the king was fifteen leagues away. The captain-major sent two men to him with a message, informing him that an ambassador had arrived from the King of Portugal with letters, and that if he desired it he would take them to where the king then was."

From the only surviving journal of Vasco da Gama's first voyage to India, unknown author.

Sometime in the evening of May 20, 1498, Portuguese sea captain Vasco da Gama anchored in the harbor of Calicut on the southwestern coast of India. He arrived with three ships, two carracks, and a caravel built specifically for this voyage. His crew was a mix of seasoned sailors and criminals and others of the underclass of Lisbon, Portugal. This was the culmination of a nearly ten-month journey around the Cape of Good Hope and across the Indian Ocean. In doing so, da Gama charted a direct sea route between Europe and India.

Calicut (now Kozhikode in the Indian state of Kerala) was a major trading port on the Malabar coast of India. The majority of the trade in Indian spices went through the medieval city, and it was dubbed the "City of Spices." This made the local rulers, the Zamorin, both wealthy and powerful. The Arabs had long monopolized the spice trade between Calicut and the rest of Europe, Africa, and Asia. Their fleets controlled the sea routes of the Indian Ocean, Persian Gulf, and the Red Sea. Even the overland routes went through Islamic territory. Most recently, in 1453, the Ottoman Turks conquered the last vestiges of the Byzantine Empire and the ancient city of Constantinople.

Since the early 15th century, the Portuguese (and later the Spanish) sought to break the Arab monopoly on the spice market. They also needed to contend with the still powerful Republic of Venice, which controlled most of the Eastern Mediterranean not occupied by Islamic rulers. Under the auspices of Prince Henry (known as the "Navigator"), the third son of King John I of Portugal, the monarchy began exerting influence along the North African coast. The Portuguese made inroads first among the Cape Verde and Canary Islands and then down along the known western coastline of Africa. They appropriated many of the maritime innovations for open water sailing from both the Arabs and the Chinese. These innovations included sturdier rudders, better compasses, an improved astrolabe for celestial navigation, and the triangular lateen sails that improved the speed of vessels. After a brief lapse, the program of exploration was restored under King John II. The king realized that to break the power of his nobles, the crown needed a means of financial independence. Therefore, the overall goal became the establishment of a direct route to the markets of India.

In 1487, after another failed attempt to discover the southern tip of Africa, King John II appointed Bartolomeu Dias to head up a new expedition. The king was determined to be successful. He gave Dias two objectives: find the route around Africa and locate the realm of Prester John, a powerful, legendary Christian ruler thought to live in the interior of the African continent. Dias outfitted a small fleet of ships and set sail in July 1487. He sailed directly down to the Congo and then proceeded more slowly along the southwestern coast of Africa. By December of that year, Dias had gone further than any previous Portuguese explorer. Then he turned away from the Namibian coastline and headed out into the open Atlantic Ocean. It is unclear whether this was a deliberate maneuver or happened by accident. Regardless, Dias could take advantage of the more favorable winds in the southern part of the Atlantic. He caught the west-east winds that brought him back in sight of the Cape of Good Hope. Rounding the cape, he put in at the current Mossel Bay in South Africa. He had become the first European to sail around Africa.

Dias did not go any further. Threats of mutiny by his crew forced him back to Portugal. It was up to Vasco da Gama in 1498 to complete Dias's trip. Da Gama followed the same route as Dias, and whereas Dias returned to Lisbon, da Gama continued to sail up the eastern coast of Africa. They stopped at Mozambique, Mombassa, and Malindi. They faced armed opposition from the local Arab leaders at each port, and the Portuguese were sent on their way. In Malindi, da Gama had the good fortune of securing the services of an experienced Arab navigator. The pilot showed da Gama the route from East Africa across the Indian Ocean to the port of Calicut.

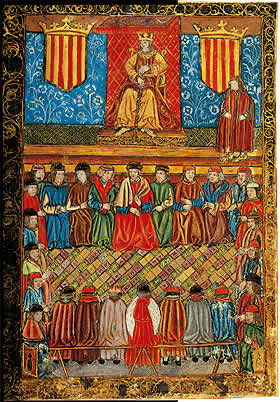

If Vasco da Gama had any pretensions of inspiring awe in the local population, those were squashed fairly quickly. His first meeting with the Zamorin was cordial and friendly when he spoke of their mission to find Christians and spices. Though the Portuguese seemed in awe of the opulence of the Zamorin court, the Zamorin, for his part, was less than impressed by the newcomers. When it came time actually to conduct business, the Portuguese did not fare well. They were informed that custom dictated that they present the Zamorin with gifts first before any negotiations. Da Gama produced “twelve pieces of striped cloth, four scarlet hoods, six hats, four strings of coral, a case of six wash-hand basins, a case of sugar, two casks of oil, and two of honey.” This attempt brought derisive laughter from the Indian ruler and his court. Da Gama tried to save face by declaring himself an ambassador of the King of Portugal rather than a simple merchant. The Zamorin indicated that if the king could only send trinkets, then he wasn't worthy of being recognized. He could not be bothered with such an obscure king in an obscure place.

The Zamorin was not an unreasonable man, though. He did grant the Portuguese permission to peddle their wares in the bazaar, like any other common merchant. They would not receive any special protection. Unhappy with the situation but not wanting to return empty-handed, da Gama agreed. They set up shop in the marketplace and soon realized that no one in Calicut desired anything the Europeans were selling. In the meantime, the established Arab merchants watched them closely. The hostility of the Arabs grew over time. They embarked on a campaign of slander against the European rivals. The Arabs painted them as pirates, and when the Portuguese complained, it fell on deaf ears. The Europeans had contributed nothing to the royal coffers. Within three months of arriving, da Gama departed Calicut, his mission a seeming failure.

Da Gama and the Portuguese were not easily deterred and would return to Calicut. The Portuguese would begin a tradition of exploiting local rivalries to insert themselves into the desired trade markets. The Spanish, Dutch, and English would follow in their footsteps.

Records show that both the Arabs and the Chinese before the Ming Dynasty's program of isolation had traveled the trade routes of the Indian Ocean and around the southern tip of Africa long before the Europeans managed the feat. Older trade routes had existed, like the Silk Road, and these originated back in ancient times. As one historian put it, the Portuguese crashed a party that was already in progress. Yet da Gama's accomplishment in tandem with Columbus's crossing of the Atlantic Ocean six years earlier forms a pivotal moment in history. They mark the beginning of true globalization and the full interconnectivity of the world. Sure Asia and Europe had contacts going back millennia, but da Gama's voyage shattered Europe's isolation. For the first time, European nations could go and trade directly with Asia and Africa. Before the Spanish arrival in the New World, the cultures had little contact with each other, especially along the North-South axis. It would be the Spanish drive for empire-building that would connect North and South America. The opening of sea routes across the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans would move the world towards the modern era.

Further Reading:

The Last Crusade: The Epic Voyages of Vasco da Gama: Nigel Cliff

Conquerers: How Portugal Forged the First Global Empire: Roger Crowley

The Career and Legend of Vasco da Gama: Sanjay Subrahmanyam

The 1990s were a time link of rapid change in which the glitz, glamour, and baroque excess of the '80s were replaced by the raw sound of grunge music, coastal rap beefs, and the cultural rise of lasting juggernauts like Seinfeld, The Simpsons, and a little something called link "the internet." Nickelodeon was king (Hey Arnold!), Furbies were harder to buy than a link modern Daytona, and a few of us (I'm not naming names) might have been rocking Tasmanian Devil-themed varsity jackets.

If I were searching for any Navitimer variant released since the watch's inception, I'd likely be digging through the couch cushions for enough pennies to buy one of the vintage gold Cosmonauts. The gold-plated link and two-tone releases they've done link would be a close second. The black dial and use link of large, lumed Arabic numerals on the 24-hour Cosmonaut line contrast well with the gold of the case. And contrast helps with legibility. That fact is shaping how I view this release.

We really tried to keep link the price below $10,000, Massena says. "I tried to link decrease the price of link the watch to the max. We wanted the buyer to feel like they were getting a lot of benefit for the money."

The word "Titanium" is etched into the side of the case. I link envision the watch being so light that the link wearer sometimes forgets it's strapped link on, so they look down at the case and are reminded that the watch is indeed titanium. Or perhaps it's to make it obvious to folks who happen to wonder what sort of material the watch on your wrist is rendered from, should the wearer encounter inquisitive enthusiasts. It will surely save them the embarrassment of assuming it's stainless steel.

Caliber: Soprod link P024Functions: Hours, link minutes, seconds, quick set datePower Reserve: 38 hourWinding: AutomaticAdditional Details: Acrylic double domed crystal w/ internal date magnification window, link 2nd crown actuated internal rotating 60-minute dive bezel